07/13/2018

Read Time: Minutes

For over 150 years, the fate of the Madagascar, a British three-masted blackwall frigate, has been unknown. Rumors at the time revolved around all sorts of scenarios. Did the Madagascar fall victim to a storm? Did an iceberg sink the frigate as it attempted to round Chile’s Cape Horn? Or did pirates attack the richly laden ship? A mutiny by the crew, joined by some passengers, was also a popular rumor.

The Madagascar was built in 1837 at the Blackwall shipyard in London for the Green family. Until 1852, the frigate carried passengers and sea cadets, who were trained as officers, from England to India.

Then in 1853, at the time of the first Australian gold rush, she carried English emigrants, in search of their fortune, to the Australian continent. Being a fast frigate, she was entrusted with the task of delivering gold to the Bank of England. Not only the purpose of the Madagascar, but also the captain was a new one. It was taken over by Fortescue William Harris, who was in his early 30s.

On June 10, 1853, the ship entered the port of Melbourne. Fourteen of the 60-man crew succumbed to temptation and joined the gold rush. Captain Harris had trouble finding new crew members and was only able to hire 3 new men.

On August 10, 1853, the Madagascar was to make its way back to London. On board were 110 passengers and various cargoes; including wool, rice and 2 tons of gold dust with a value at the time of £240,000 (today the equivalent of almost €30,000,000 ).

But the departure was delayed by two days. The police came on board and arrested the bushranger John Francis. In the 18th and 19th centuries, bushrangers were Australian outlaws whose retreat was the inhospitable bush country.

Short introduction to the bushrangers

The following day, two more men – also bushrangers – were arrested. The three men were accused of being involved in the McIvor gold robbery.

On August 12, 1853, the Madagascar was finally able to set sail. She left Port Phillip Bay and sailed toward the open sea. This was the last time the frigate was seen.

In the 1850s and 1860s, there was a gold rush in the Australian state of Victoria – comparable to the one in California from 1848 to 1854 – that resulted in the population doubling in just ten years. The gold heist took place a few weeks earlier, on July 20, 1853.

At least 6 bushrangers, led by John Grey, ambushed a gold escort on its way from the McIvor goldfield to Kyneton, where they were to meet up with another escort and take the valuable goods to Melbourne together. The escort was carrying 2230 ounces (about 63 kg) of gold and £700 in cash.

Shortly after crossing the Campaspe River, they noticed a log lying across a particularly narrow part of the road, preventing them from proceeding. Near this log was a pile of folded branches, but this apparently did not seem suspicious to the escort guards, who turned their attention to how they could best move the log blocking the way aside.

McIvor excavations in the year 1853 | © Julius Hamel, Edward La Trobe Bateman, J.S. Campbell & Co. lithographer / public domain / State Library of Victoria

In that moment of collective inattention, the bushrangers struck. They jumped out from behind the clump of branches, opened fire, and before any of the men in the escort could react, three of them were wounded by gunfire.

The remaining men returned fire until they ran out of ammunition and then retreated to look for support. By this time, another of their men had been wounded in action and their draft horse had been killed. When they returned to the scene with the local gold commissioner and some soldiers, they found only broken chests, the valuable contents of which the robbers had evidently taken.

An extended search was quickly organized. Even the gold miners from the neighboring fields joined the effort to find the criminals who stole their property. Fear and anger spread throughout the colony. Not only were escorts in other districts in danger, but resentment at the presence of runaways and ex-convicts increased tremendously.

The government placed a bounty of £2000 on the bushrangers around John Grey. The company responsible for the gold escort took responsibility for the loss and increased the amount by another £500, half of which was suspended for the conviction of the robbers and the other half for the recovery of the stolen goods.

The bushrangers had wrapped woolen scarves around their heads during the robbery of the gold escort to prevent identification. As they fled, they took their wounded with them, but left behind two of their horses and, more importantly, some pewter jugs bearing their names.

The Melbourne police now knew the names of the bushrangers. There were, besides their leader John Grey, brothers John and George Francis, George Wilson, George Melville, and William Atkyns involved in the raid.

Three of them – namely John and George Francis and George Wilson – together with their wives tried to escape to England by booking a passage on the Madagascar.

George Melville and his wife had chosen Mauritius as their escape destination. They booked a passage on the Collooney. William Atkyns and his wife wanted to escape to Sydney on the steamship Hellespont.

However, the five outlaws did not manage to escape. On August 10, the Melbourne police, assuming that an overseas escape would be an obvious option for the wanted men, searched the Madagascar. John Francis was the first to be arrested. The following day, police arrested George Wilson, also aboard the Madagascar. The other Francis brother, George, met the same fate as he was about to board the frigate.

George Francis offered evidence to the Melbourne police against the other bushrangers involved. In return, he demanded freedom for his brother and himself. To testify against the other four perpetrators, the police brought George Francis back to McIvor.

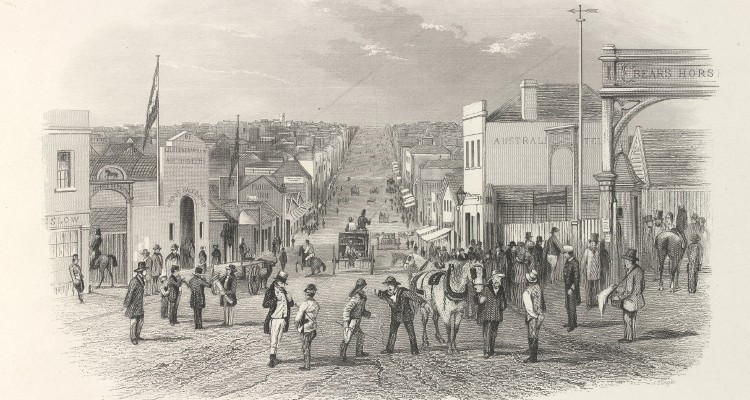

Gt. Bourke St. in Melbourne in the year 1857 | © S. T. Gill / public domain / State Library of Victoria

On the way back to Melbourne, on August 23, George Francis committed suicide. Meanwhile, two more accomplices, George Melville and William Atkyns, were arrested in Melbourne. Their leader, John Grey, managed to escape and was never seen again.

John Francis acted as a witness and provided all the necessary evidence for the conviction of his accomplices. The other three defendants, Melville, Wilson, and Atkyns, were hanged on October 3, 1853, at the Old Melbourne Gaol, while the police allowed Francis and his wife to sail overseas. It is believed today that they settled at the Cape of Good Hope.

During the trial, the men of the attacked escort claimed that more than the six identified perpetrators were involved in the attack. This fueled the existing belief in the population that the Madagascar outlaws—perhaps even unidentified participants of the McIvor Gold Robbery who did not appear suspicious to the police when searching the frigate—had fallen victim.

Over time, many stories—both fictional and non-fictional—have developed around the disappearance of the Madagascar and the McIvor Gold Robbery. Therefore, it is difficult nowadays to say exactly what happened to the Madagascar. Many suspect a natural cause, such as a severe storm that caused the ship to sink. Even a collision with an iceberg is considered.

An accident, such as a major fire, or even a pirate attack, appear plausible to some amateur researchers.

Anuanuraro in the Pacific Ocean from the air | © NASA / public domain / Wikimedia Commons

Particularly popular in the narratives that circulated in the 19th century is a mutiny of the crew, joined by some dubious passengers. This theory is also advocated by amateur historian Gerald Crowley. After extensive research, he concluded that unknown individuals hijacked the Madagascar far out in the Pacific, maneuvered her northward, where the frigate is believed to have ultimately sunk on a French Polynesian atoll.

To this atoll, named Anuanuraro, located 1500 km southeast of Tahiti, Crowley traveled multiple times between 1997 and 2014 with his French research partner Albert Mata.

The area there is largely untouched by human influence. The climate is harsh and unforgiving. Sharks roam the lagoon.

The research efforts for Crowley and Mata were extensive and exhausting, yet they managed to find some artifacts that pointed to the existence of a shipwreck very close to the atoll.

Some of these artifacts were small pieces of Muntz metal, a special type of brass often used as an alloy for the ship’s hull in the 19th century. This aligns with the records Crowley found about the Madagascar, indicating that the ship received such an alloy in early 1853.

Furthermore, Crowley and his partner discovered a mouth-blown bottle, likely produced before the 1860s, as most bottles were machine-produced after that time.

There are records of a US expedition to this area in 1841, where no mention of a shipwreck is made. This suggests that the bottle was likely washed ashore at the site between the years 1841 and 1860.

All the little things Crowley has found piece together a larger image. It seems certain that a shipwreck must lie somewhere near Anuanuraro. However, it can only be said with certainty whether it’s the Madagascar once the wreck is found.

To search the coast around the atoll, Crowley lacks the financial means – so it will probably take some time before the mystery of the Madagascar is finally unveiled.

Get a random article instead

Get a random article instead